Ashley Blaker is a comedian and a writer. He’s also a parent to six children, three of whom have a special educational needs diagnosis (SEND). When Ashley’s eldest son Adam was diagnosed with ADHD and autism sixteen years ago at the age of three, he scanned the shelves and turned to the Internet to look for advice but could only seem to find information that was very negative.

“At that time, I read quite a few books and we looked online as much as we could to see what was out there. Everything I read was very depressing, very worrying. And so I wanted to write a book to help other parents. This is basically the book that I wish I had read 16 years ago.”

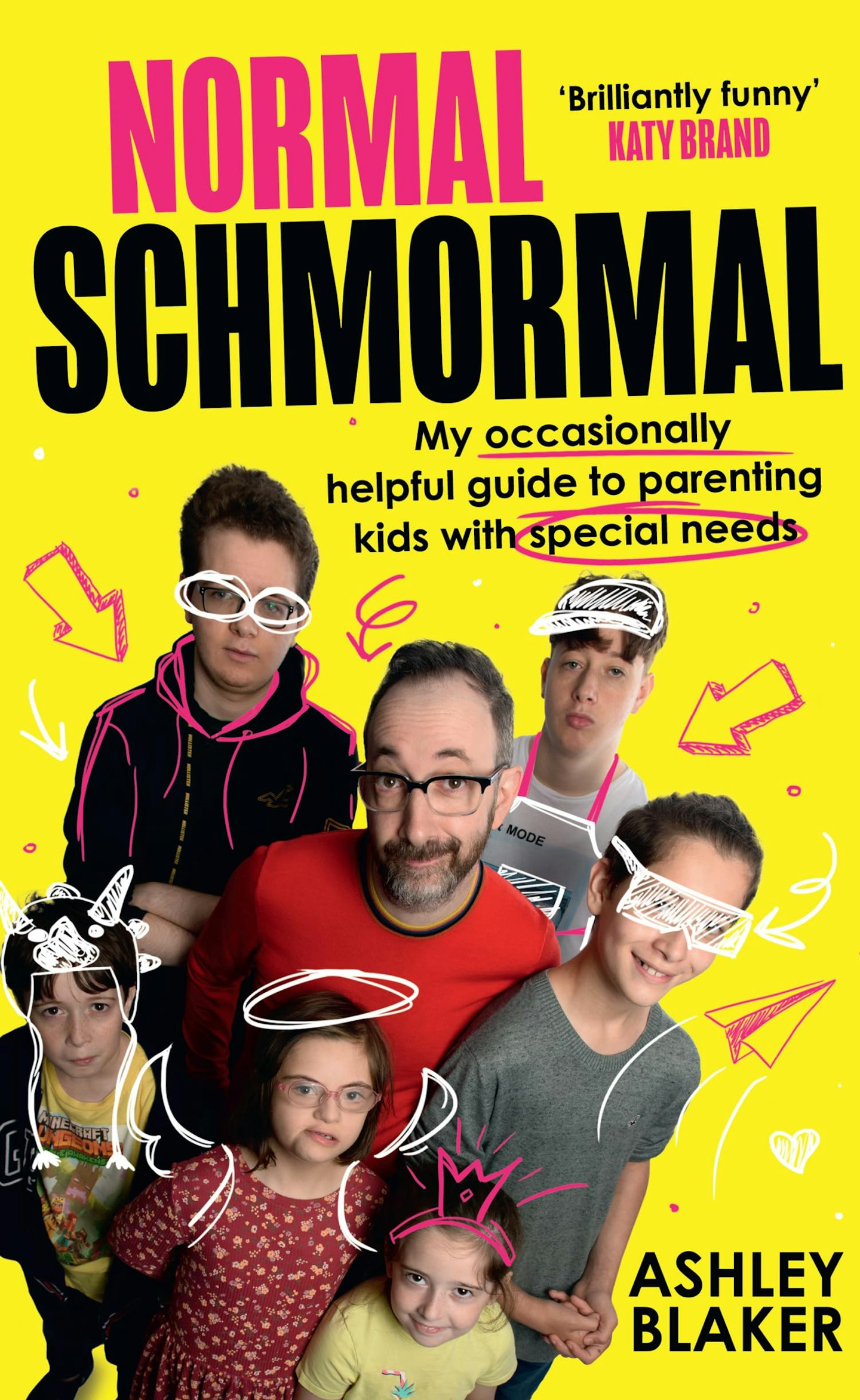

Part-memoir, part-guide, Ashley's book Normal Schmormal is written in an A-Z format "but appropriately for a book about children who might have a learning difficulty, it's all jumbled up in in the wrong order. So the first chapter is M for Meetings, Meetings, Meetings, the last chapter is O for Onwards and Upwards."

One of the chapters is called No Room At The Inn and explains the struggles that Ashley and his wife faced when trying to find the right school place for their son. "My daughter with Down's syndrome goes to a special school, no questions, that's the right place for her. My third son goes to a mainstream school, he qualifies for a bit of extra support."

But when they tried to find a suitable school for Adam, it was a struggle. "He qualified for full support. I think that's like 35 hours. His needs are not sufficiently demanding; they're not for a special school, but neither are they quite right for a mainstream school. He falls somewhere in between the two and these are the children when it comes to schools who are the hardest to place."

"It was quite traumatic to relive some things"

He goes on to talk about how this section of the book was hard to write but important to include. "I had forgotten how painful it was. It really was one of the most challenging few months. In order to write this chapter, I had to go back in time. I'd kept everything - his statement of special educational needs and the paperwork and the emails back and forth with our local authority and the primary school and all these things. So, it was quite traumatic for me in a way to relive some of the things which I hadn't thought about for a long time."

He makes the valid point that the mainstream school system isn't always the best place for every child. "We may have to accept that there are some people who just aren't made for school and that that's fine, you know. You can't mould everyone to a cookie-cutter shape."

Although Ashley isn't afraid to shy away from the more difficult topics, his writing is also filled with happy memories and humour too. "I certainly don't shirk all the many challenges involved, but even so, the core thread running through the book is one of positivity and joy and acceptance."

When talking about what it's like to be a parent to a child with disabilities he says, "There are so many things to worry about. You may worry whether your child will ever get a job, whether they'll ever be able to live independently, whether they'll ever be able to get married, whether they'll live beyond their late teens. There's so much to worry about that you'd barely be able to get through the day if you constantly worried about the big things."

"The adoption assessment for Zoe was very full on"

Ashley and his wife adopted their daughter Zoe who has Down's syndrome in 2010 when she was just one year old after spotting an adoption advert in their local paper.

He details some of the lengthy process in his book. "I feel for people who are not able to have biological children who are going through this process as the assessment was very full on. The level of detail they want to know about you is a lot, but you can understand why they do it as children who are adopted are often among the most vulnerable.

"They ask you questions like 'When you were in primary school, did you get invited to many birthday parties?'. I remember thinking why is this important whether 30 years ago, I ate enough jelly? There were multiple choice questions like 'If a child's favourite cereal ran out, what would you do? Would you go to the shops? Would you make them go hungry? Would you give them dog food?'"

"I've learnt to adapt, and embrace who they are"

When parenting children with SEND, it's about making adaptions. "We are Jewish, my eldest son refused to attend his own Bar Mitzvah. So we had to rethink it. You might have, like preconceived visions of what your child's Bar Mitzvah would look like, but no, you'd have to ditch those and kind of come up with something different."

While there are many challenges that come with raising SEND children, Ashley says it's important to remember that they see the world differently to you and that it's no bad thing that needs 'fixing'.

"We've spent many years seeing if there were any ways to fix our son and then we came to a place of realising he isn't a problem to solve. This is who he is, and we need to embrace it.”

"Every stage of life involves some kind of challenge. I suppose it comes down to it, I use this word 'diversity'. It's a word that's used a lot in modern day life, and people like to think of themselves as being diverse. We're used to diversity in the sense of turning on TV and seeing people who don't necessarily look like us, but people in their own lives tend to like people who are very much like them. And I think one thing we have had to really embrace is diversity.

"Our children aren't necessarily like us. I have two children with autism and ADHD, and they're very different to each other. So diversity is accepting very different people, and I think is a crucial part of the journey."