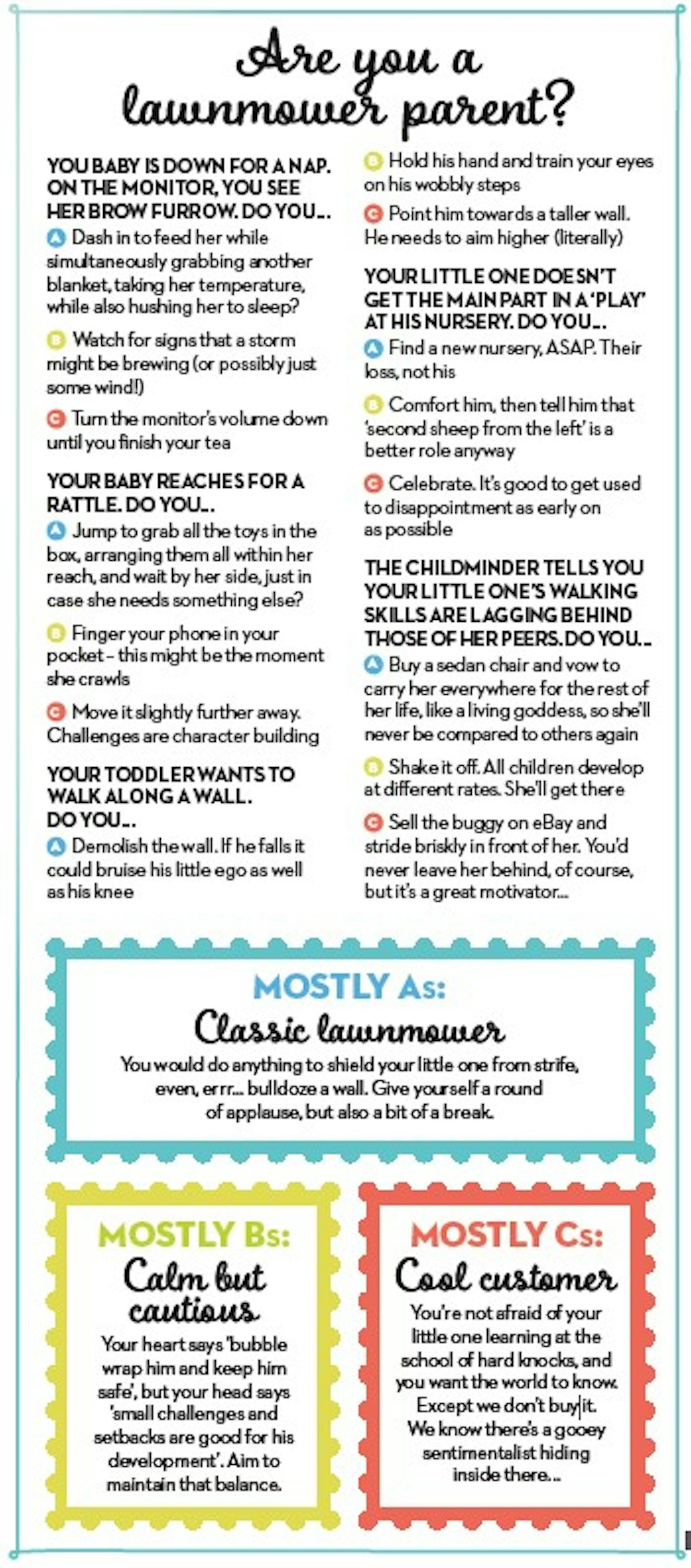

Guilty of mowing down every obstacle your tot encounters? Step back now and you’ll help build resilience for life.

Your precious princess is trying to get her arms into her coat. The coat, however, is not co-operating. Her face crumbles, a storm brews on her brow. But what’s this? Supermummy to the rescue! You grab the coat, gently guiding her arm in. Her brow smooths. All is well with the world again…. Or is it? Have you helped your little one or have you, actually, unwittingly practiced the latest parenting taboo… lawnmowing?

Lawnmower mums mow down all the obstacles in their child’s path, so that little Theo or Thea never has to experience any discomfort or frustration. It is, of course, an entirely well-meaning and very common impulse. Who wants to see their baby struggling and unhappy? But a growing body of thinking suggests that jumping in too soon to smooth things over may actually rob your child of important experiences, ones that foster vital physical, cognitive and emotional skills.

‘As parents, we want to keep our kids safe and protect them,’ says Abigail Wright, an educational psychologist specialising in the early years. ‘There’s a natural tendency to jump in.’ And as a mum to a three-year-old and three-month-old, Abigail knows just what it is like when your to-do list is long and the pressure is on (always, in other words). Jumping in to intervene can sometimes feel like it will make our job easier – anything to avoid a meltdown!

-

Read more: Pinpoint your toddler's tantrums

It may, however, make the job much harder in the long term. Think back to that original scenario, and the fight with the coat. Slowing down, stepping back and letting your little one persevere might mean that, in a few weeks, she learns how to match arm with arm hole. Suddenly, that’s one less thing you need to do before leaving the house. Plus, says Abigail, in being handed the chance to wrestle with a coat, your little one will learn fine and gross motor skills, spatial awareness, problem-solving skills, and build self-esteem and all-important resilience. ‘She will know that, when faced with a problem or a stressful situation, she’s up to the challenge,’ adds Abigail.

Still tempted to jump in? Over the last decade, resilience has become a buzzword in educational and developmental psychology circles. The ability to approach a challenge with enthusiasm, fail, dust yourself off and try again is, many now think, one of the most important skills a child can learn. As computers become increasingly able to perform an number of jobs, the future economy will rest more and more on emotional intelligence and creativity. Resilience is likely to be one of the core skills required.

-

Read more: What is Kiddle?

Sure, you might be thinking, but she’s only two. Can’t all that wait? Won’t she feel abandoned if I don’t jump in? In fact, it may be just the opposite. Anthropologist Anna Machin has devoted her career to studying the parental bond, in a variety of species and in countries around the world. Her research suggests that the deeper, warmer and more responsive the bond (or emotional attachment), the more able a child is to detach themselves early and explore their own independence.

Developmental psychologist Emmy Werner, meanwhile, is an expert in resilience and has studied its roots. Her research suggests that resilience can indeed result from a strong bond with a caregiver. She also found that resilient children tend to have an ‘internal locus of control’. In other words, they see themselves in charge of their own destiny. That’s a learnt trait, one you can start teaching from your little one’s earliest years. And one way to do that is to encourage them to tackle challenges that Abigail describes as being ‘just within their zone of proximal development.’

We’re not talking about encouraging your toddler to walk a high wire or feed a lion but, instead, giving them opportunities to try their hand at safe challenges – ‘Ones that are just outside their current ability,’ says Abigail. And, don’t worry, you will still have a very active role in encouraging this independence – it is just a little more covert. Less lawnmower and more, in Abigail’s words: ‘scaffolding’. ‘You wouldn’t just say: right get your shoes on, let’s go, to a two-year-old who doesn’t have the skills yet,’ explains Abigail. Instead, helping them to master this big skill involves breaking it down into little ones: ‘So you might say: slide your feet in, that’s it. Now can you pull the Velcro across?’

This gentle, loving ‘scaffolding’ of their independence can begin even before your little one learns to crawl. Imagine your baby is on a playmat and a rattle is just out of her reach. Pause before jumping up, immediately, to move it in front of her. ‘Babies take longer to process objects in their environment,’ says Abigail. ‘If you hand it to her immediately, she may not have had time to register the object and process her desire for it.’ Instead, focus your efforts on ‘tuning in to those emotions. If she just seems interested and reaching, it’s great to let her try and practice her motor skills and getting mobile. When she starts showing signs of frustration or tiredness, that’s the point to step in and help.’

Weaning is another great example. Everyone has their own way of doing it, and none is better than any other. If you are up for it, however, there’s value in letting her try to pick that carrot stick up, and sitting back while she chases it around the plate for ten minutes. Moreover, when it falls on the floor, do not look at this as a failure or even a shame. Instead, see at as a step on the road to independence. ‘She’s developing spatial and sensory awareness, co-ordination and an early sense of autonomy,’ says Abigail. It’s a win, albeit a messy one.

When the carrot finally makes it to the mouth, it is a big cause of celebration. ‘Yet the important thing with praise is to focus on the effort,’ says Abigail. You do not want her to absorb the idea that perfection is the goal, and that nothing less will do. Instead, you want to fuel their intrinsic motivation, or their love of taking on a challenge for the sake of it.

In fact, Abigail suggests the lesson is deeper still. As your baby grows into a toddler, not only is it a good idea to normalise difficult situations, but we could all use these challenges to normalise the difficult emotions they provoke, too. When your three-year-old struggles to scale the big climbing frame, do the buttons on her cardigan or grip a crayon, it’s tempting to distract them from those feelings of frustration, anger or sadness, says Abigail. ‘But we can use these moments as opportunities to connect. You can say: “Oh yes, I can see that must have hurt or been really frustrating,” and then help them to find good solutions.’ Do that, and next time the situation arises, your little one is more likely to have the confidence, self-soothing tactics and tools to tackle it instead of reacting with challenging behaviour.

‘There’s no such thing as failure for children, as long as they are happy and safe,’ says Abigail. ‘Letting them experience things not going right is how we help them to learn. Later in life, they’ll know that they can take on a big challenge, head on and without fear.’ But first, let’s start with that coat.

More from Mother&Baby

-

What are your favourite cleaning tips and products? Let us know on Twitter! And while you're there, follow us on Instagram and Facebook too!

-

Why not join thousands of mums and start your very own Amazon Baby Wish List? They're absolutely free to create and perfect to send to your family, friends, and colleagues to make sure you're getting the baby products you really need... Click here!