If your baby needs some help to be born during labour, your obstetrician may use a ventouse to deliver him.

With around one in eight women having an assisted birth, it’s possible that you may end up having a forceps or ventouse delivery, even if you've planned to have a 'natural' vaginal birth.

If you're keen to be prepared for every eventuality when you give birth, we've rounded up everything you need to know about having a ventouse delivery, with expert advice from consultant obstetrician, Christian Barnick.

When is a ventouse assisted birth required?

It’s usually because you’ve been pushing for a few hours, but your baby is not coming out, or if shoulder dystocia occurs or if your baby is becoming distressed and needs to be born quickly.

‘Your baby needs to be in good shape for a ventouse delivery – this means that he has a healthy heart rate and is not too distressed,’ says Christian, a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at The Portland Hospital. ‘You need to be 10cm dilated and your baby’s head needs to be at the opening of the cervix and fully engaged.’

Most doctors choose a ventouse delivery before trying forceps as there’s less risk of tearing. ‘But if you’re less than 34 weeks pregnant, you can’t use a ventouse as your baby’s skull is too soft and it could be damaged,’ says Christian.

Your obstetrician or midwife should always make the reasons for you needing an assisted birth very clear and your consent will be needed before the procedure begins.

What is a ventouse?

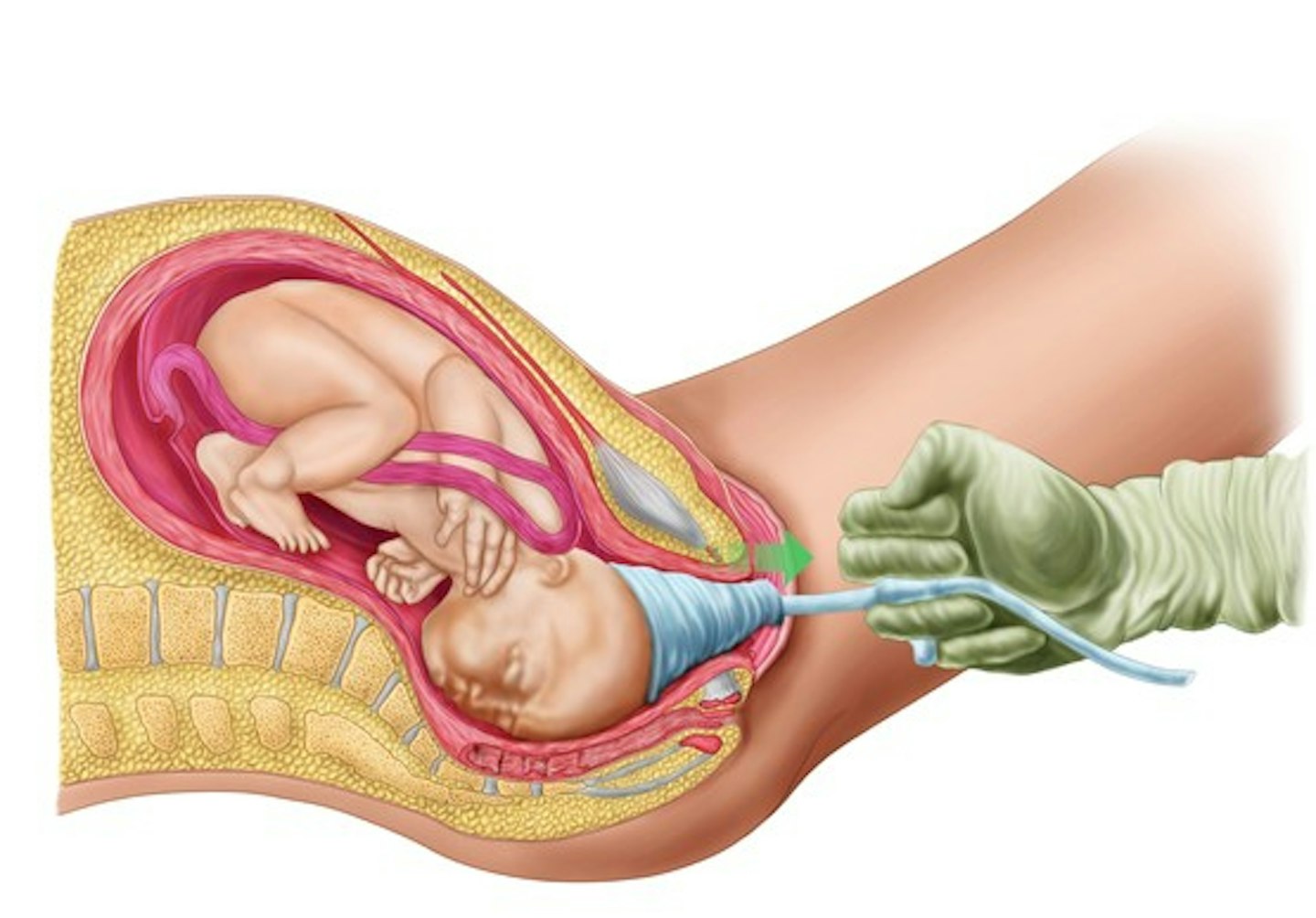

'A ventouse is a small cup that fits on the back of your baby’s head and is attached to a suction device,’ says Christian.

‘A vacuum is created using either a hand-held pump so that your doctor can then gently pull your baby out.’

What happens during a ventouse assisted birth?

‘The obstetrician will insert the ventouse so it’s fitted to the back of your baby’s head, and then turn on the suction,’ says Christian. ‘When you have a contraction, he’ll start pulling the ventouse to ease your baby out. He can’t pull too hard as he’ll lose the suction.’

Throughout the delivery, your obstetrician should be chatting to you explaining what is happening.

Your pain relief

While a ventouse delivery is less invasive and painful than using forceps, you may prefer to have some pain relief before the ventouse is inserted. ‘We’d usually recommend an epidural if this hasn’t already been given, or a pudendal block. This is when the anaesthetic is injected into a nerve in your vaginal wall to numb any pain,’ says Christian. While an epidural will numb the whole area, if the birthing team are in a rush to get your baby out, there may not be time for an anaesthetist to come down to administer it, and a pudendal block will be faster.

What happens after the birth?

‘When your baby is handed to you, he may have a small bump on his head where the ventouse was attached,’ says Christian. ‘This is known as a chignon, and it’s caused by the suction drawing the scalp up. Don’t worry too much as the bump will go down after about 30 minutes. There may also be a small bruise and this will disappear after a day or two.’

A ventouse delivery is good for mum and baby if there is no rush for him to be born, as it takes longer than forceps but is less likely to damage your vaginal wall or result in an episiotomy.

What are the risks?

According to the NHS, there are a number of risks involved when it comes to having a ventouse assisted birth.

• Vaginal tearing or episiotomy which require stitches after birth

• 3rd or 4th degree vaginal tear - this involves a tear to the rectum

• Anal incontinence

• Urinary incontinence

• Higher risk of blood clots

The risks to your baby are very minimal, and other than small bruises and a bump on your baby's head, they should be fine.